You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

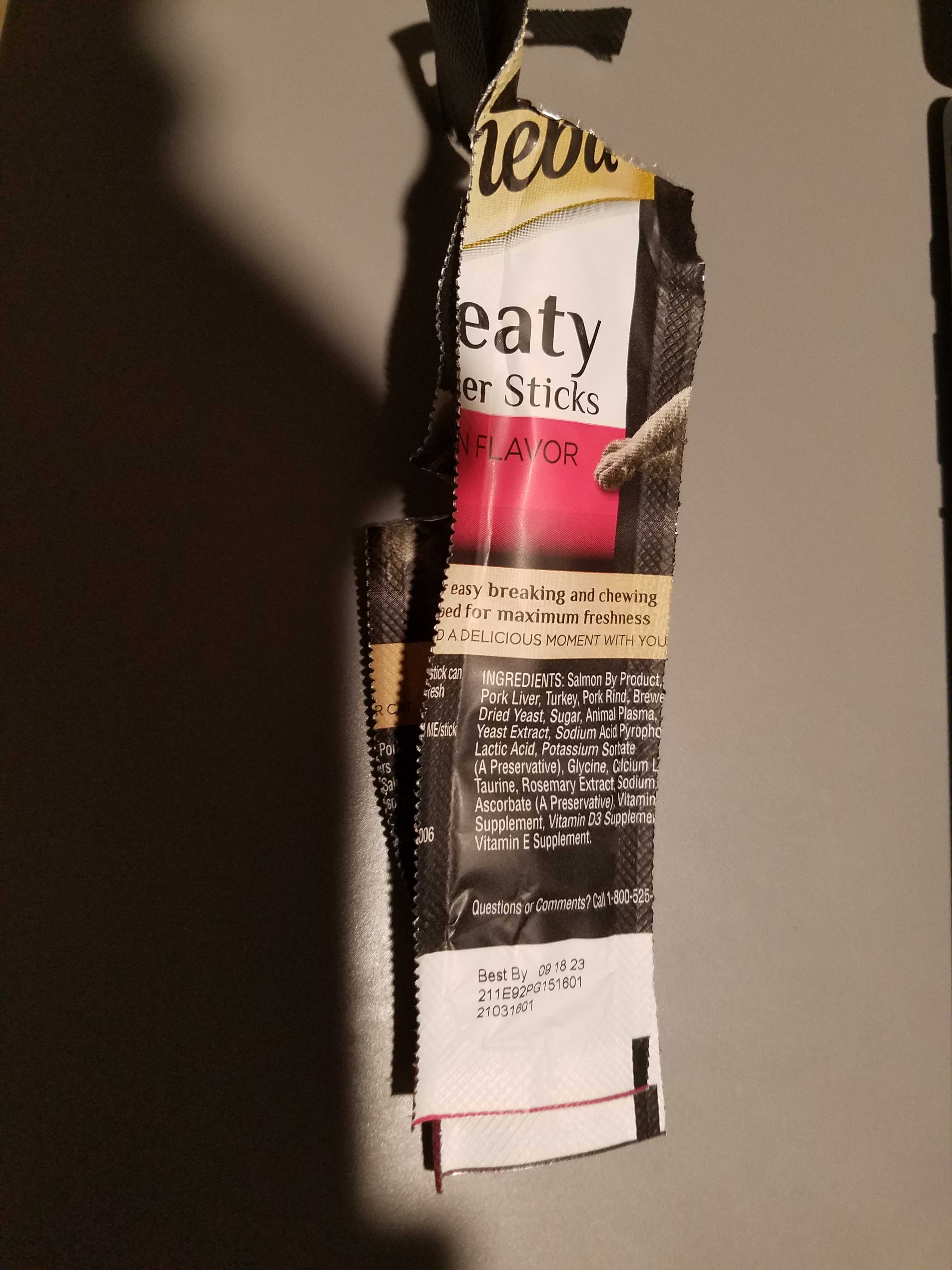

It's What Cats Crave....

- Thread starter Macrobius

- Start date

Feline Brawndo?

Gawn Chippin

Arachnocronymic Metaphoron

Real cats like their meals fresh

Lord Osmund de Ixabert

I X A B E R T.com

The optimal nourishment one can furnish to felines and canines mirrors that of mankind: exclusively, raw carnage.

well there is the problem of parasites thoThe optimal nourishment one can furnish to felines and canines mirrors that of mankind: exclusively, raw carnage.

I dont agree that raw meat is best for humans, at least most people living in civilized areas, who hav grown adapted to clean water and food

But for cats yea, fresh meat is definitely best if not diseased

Lord Osmund de Ixabert

I X A B E R T.com

There's the non-problem of parasites, which only feed on the vegetable matter that you can't digest, and generally originate in grains.

Gawn Chippin

Arachnocronymic Metaphoron

Gawn Chippin

Arachnocronymic Metaphoron

Tonight I had a visit from Silvestro, was very hungry but I had no meat to give.

Gave him a lot of fat cubes from a salame toscano and some slices of salame di Felino*.

I was afraid of the amount of salt, then I gave him butter, and tuna in the end.

He finished everything and now is sleepin' on a cuccia I made on the stairs.

*Salame Felino is a very fine one, made in a small town in the province of Parma called Felino, not made of cats; the origin of the name is uncertain and no one attributes it to the felix -- but I would say that it must have something to do with cats, considering that a small fraction of Felino is called San Michele dei Gatti.

Last edited:

Macrobius

Megaphoron

Important info on cats:

Ambrosius Macrobius on Gab: 'The most important important poast you will ever …'

Ambrosius Macrobius on Gab: 'The most important important poast you will ever see from this account. Why? When Adam delved and Eve span / who was then a Gentleman? Adam's job was to look after the plants and animals in Paradise. Christian monks know this...

The most important important poast you will ever see from this account. Why?

When Adam delved and Eve span / who was then a Gentleman?

Adam's job was to look after the plants and animals in Paradise.

Eve was the distaff side.

Important memo about 'St Distaff's Day' and Orthodox Christian Christmas @Nikephoros II Phokas https://www.thebookofdays.com/months/jan/7.htm

ST. DISTAFF'S DAY

As the first free day after the twelve by which Christmas was formerly celebrated, the 7th of January was a notable one among our ancestors. They jocularly called it St. Distaff's Dag, or Rock Dag, because by women the rock or distaff was then resumed, or proposed to be so. The duty seems to have been considered a dubious one, and when it was complied with, the ploughmen, who on their part scarcely felt called upon on this day to resume work, made it their sport to set the flax a-burning; in requital of which prank, the maids soused the men from the water-pails. Herrick gives its the popular ritual of the day in some of his cheerful stanzas:

This mirthful observance recalls a time when spinning was the occupation of almost all women who had not anything else to do, or during the intervals of other and more serious work�a cheering resource to the solitary female in all ranks of life, an enlivenment to every fireside scene. To spin�how essentially was the idea at one time associated with the female sex! even to that extent, that in England spinster was a recognized legal term for an unmarried woman�the spear side and the distaff side were legal terms to distinguish the inheritance of male from that of female children�and the distaff became a synonym for woman herself: thus, the French proverb was:St. Distaff's Day; Or, the Morrow after Twelfth-day

Partly work and partly play

You must on St. Distaffs Day:

From the plough soon free your team;

Then cane home and fother them:

If the maids a-spinning go,

Burn the flax and fire the tow.

Bring in pails of water then,

Let the maids bewash the men.

Give St. Distaff' all the right:

Then bid Christmas sport good night,

And next morrow every one

To his own vocation.'

Now, through the change wrought by the organized industries of Manchester and Glasgow, the princess of the fairy tale who was destined to die by a spindle piercing her hand, might wander from the Land's End to John O' Groat's House, and never encounter an article of the kind, unless in an archaeological museum.'The crown of France never falls to the distaff.'

Mr. John Yonge Akerman, in a paper read before the Society of Antiquaries, has carefully traced the memorials of the early use of the distaff and spindle on the monuments of Egypt, in ancient mythology and ancient literature, and everywhere shews these implements as the insignia of womanhood. We scarcely needed such proof for a fact of which we have assurance in the slightest reflection on human needs and means, and the natural place of woman in human society. The distaff and spindle must, of course, have been coeval with the first efforts of our race to frame textures for the covering of their persons. for they are the very simplest arrangement for the formation of thread: the distaff, whereon to hang the flax or tow�the spindle, a loaded pin or stick, whereby to effect the twisting; the one carried under the arm, the other dangling and turning in the fingers below, and forming an axis round which to wind parcels of the thread as soon as it was made. Not wonderful is it that Solomon should speak of woman as laying her hands to the distaff (Prov. xxxi. 19), that the implement is alluded to by Homer and Herodotus, and that one of the oldest of the mythological ideas of Greece represented the Three Fates as spinning the thread of human destiny. Not very surprising is it that our own Chaucer, five hundred years ago, classed this art among the natural endowments of the fair sex in his ungallant distich:

It was admitted in those old days that a woman could not quite make a livelihood by spinning; but, says Anthony Fitzherbert, in his Boke of husbandrie 'it stoppeth a gap,' it saveth a woman from being idle, and the product was needful. No rank was above the use of the spindle. Homer's princesses only had them gilt. The lady carried her distaff in her gemmed girdle, and her spindle in her hand, when she went to spend half a day with a neighbouring friend. The farmer's wife had her maids about her in the evening, all spinning. So lately as Burns's time, when lads and lasses came together to spend an evening in social glee, each of the latter brought her spinning apparatus, or rock, and the assemblage was called a rocking:'Deceit, weeping, spinning, God hath given

To women kindly, while they may live.'

It was doubtless the same with Horace's uxor Sabina persuta solibus, as with Burns's bonnie Jean.'On Fasten's eve we had a rocking.'

The ordinary spindle, throughout all times, was a turned pin of a few inches in length, having a nick or hook at the small and upper end. by which to fasten the thread, and a load of some sort at the lower end to make it hang rightly. In very early times, and in such rude nations as the Laps, till more recent times, the load was a small perforated stone, many examples of which (called whorls) are preserved in antiquarian museums. It would seem from the Egyptian monuments as if, among those people, the whorl had been carried on the top.

Some important improvements appear to have been made in the distaff and spindle. In Stow's Chronicle, it is stated:

'About the 20th year of Henry VIII, Anthony Bonvise, an Italian, came to this land, and taught English people to spin with a distaff, at which time began the making of Devonshire kersies and Coxall clothes.' Again, Aubrey, in his Natural History of Wiltshire, says: 'The art of spinning is so much improved within these last forty years, that one pound of wool makes twice as much cloath (as to extent) as it did before the Civill Warres.'

Spinning with the Distaff |

We have, however, evidence, in a manuscript in the British Museum, written early in the fourteenth century, of the use of a spinning-wheel at that date: herein are several representations of a woman spinning with a wheel: she stands at her work, and the wheel is moved with her right hand, while with her left she twirls the spindle: this is the wheel called a torn, the term for a spinning-wheel still used in some districts of England. The spinning-wheel said to have been invented in 1533 was, doubtless, that to which women sat, and which was worked with the feet.

Spinning with the wheel was common with the recluses in England: Aubrey tells us that Wiltshire was full of religious houses, and that old Jacques 'could see from his house the nuns of Saint Mary's (juxta Kington) come forth into the Nymph Hay with their rocks and wheels to spin, and with their sewing work.' And in his MS. Natural History of Wiltshire, Aubrey says:

The change from the distaff and spindle to the spinning-wheel appears to have been almost coincident with an alteration in, or modification of, our legal phraseology, and to have abrogated the use of the word spinster when applied to single women of a certain rank. Coke says:'In the old time they used to spin with rocks; in Staffordshire, they use them still.'

Blount, in his Law Dictionary, says of spinster:'Generosus and Generosa are good additions: and, if a gentlewoman be named spinster in any original writ, etc., appeale, or indictmente, she may abate and quash the same; for she hath as good right to that addition as Baronesse, Viscountesse, Marchionesse. or Dutchesse have to theirs.'

In his Glossographia, he says of spinster:'It is the addition usually given to all unmarried women, from the Viscount's daughter downward.'

'I am unable' (says Mr. Akerman) 'to trace these distinctions to their source, but they are too remarkable, as indicating a great change of feeling among the upper classes in the sixteenth century, to be passed unnoticed. May we suppose that, among other causes, the art of printing had contributed to bring about this change, affording employment to women of condition, who now devoted themselves to reading instead of applying themselves to the primitive occupation of their grandmothers; and that the wheel and the distaff' being left to humbler hands, the time honoured name of spinster was at length considered too homely for a maiden above the common rank.'It is a term or addition in our law dialect, given in evidence and writings to a femme sole, as it were calling her spinner: and this is the only addition for all unmarried women, from the Viscount's daughter downward.'

Before the science of the moderns banished the spinning-wheel, some extraordinary feats were accomplished with it. Thus, in the year 1745, a woman at East Dereham, in Norfolk, spun a single pound of wool into a thread of 84,000 yards in length, wanting only 80 yards of 48 miles, which, at the above period, was considered a circumstance of sufficient curiosity to merit a place in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. Since that time, a young lady of Norwich has spun a pound of combed wool into a thread of 168,000 yards; and she actually produced from the same weight of cotton a thread of 203,000 yards, equal to upwards of 115 miles: this last thread, if woven, would produce about 20 yards of yard-wide muslin.

The spinning-wheel has almost left us�with the lace-pillow, the hourglass, and the hornbook; but not so on the Continent.

SERMON TO THE JEWS'The art of spinning, in one of its simplest and most primitive forms, is yet pursued in Italy, where the country-women of Cilia still turn the spindle, unrestrained by that ancient rural law which forbade its use without doors. The distaff has outlived the consular fasces, and survived the conquests of the Goth and the Hun. But rustic hands alone now sway the sceptre of Tanaquil., and all but the peasant disdain a practice which ones beguiled the leisure of high-born dames.'

7th January 1615, Mr. John Evelyn was present at a peculiar ceremony which seems to have been of annual occurrence at Rome. It was a sermon preached to a compulsory congregation of Jews, with a view to their conversion. Mr. Evelyn says:

CATTLE IN JANUARY'They are constrained to sit till the hour is done, but it is with so much malice in their countenances, spitting, humming, coughing, and motion, that it is almost impossible they should hear a word from the preacher. A conversion is very rare.'

Worthy Thomas Tusser, who, in Queen Mary's time, wrote a doggrel code of agriculture under the name of Five hundred Points of Good Husbandry recommends the farmer, as soon as Christmas observances are past, to begin to attend carefully to his stock.

He urges the gathering up of dung, the mending of hedges, and the storing of fuel, as employments for this mouth. The scarcity in those days of fodder, especially when frost lasted long, he reveals to us by his direction that all trees should be pruned of their superfluous boughs, that the cattle might browse upon them. The myrtle and ivy were the wretched fare he pointed to for the sheep. The homely verses of this old poet give us a lively idea of the difficulties of carrying cattle over the winter, before the days of field turnips, and of the miserable expedients which were had recourse to, in order to save the poor creatures from absolute starvation:'Who both by his calf and his lamb will be known,

May well kill a neat and a sheep of his own;

And he that can rear up a pig in his house,

hath cheaper his bacon and sweeter his souse.'

'From Christmas till May be well entered in,

Some cattle wax faint, and look poorly and thin;

And chiefly when prime grass at first doth appear,

Then most is the danger of all the whole year.

Take verjuice and heat it, a pint for a cow,

Bay salt, a handful, to rub tongue ye wot how:

That done with the salt, let her drink off the rest;

This many times raiseth the feeble up beast.'

Rest at the link.

- 30 -