Petr

Administrator

This thread is meant to be a re-presentation of this Old Phora thread:

Simply put, royal absolutism mightily paved the way for egalitarian mass democracy in the Western civilization by means of putting down and castrating aristocratic power, turning the noblemen into mere high-ranking servants of the crown, or mere glittering but impotent courtiers, instead of the proud and semi-independent feudal warlords they had once been. The crown also considerably curtailed clerical power - and even before the "Enlightened Absolutism" was a thing. Thus it was easy for egalitarian revolutionaries, once they had grabbed control of the centralized state machinery, to continue where the monarchs and despots had left off, considerably accelerating their policies.

The best way to introduce this topic - which boils down to the principle "High & Low against the Middle" - might be this piece written by Roland; IMHO, this is one of the most concisely insightful pieces ever written on the Old Phora, taking inspiration from the theories of Bertrand de Jouvenel:

The great French Revolution was of course a classic example of this phenomenon in action. The Victorian-era writer Charles Kingsley described how the Jacobins took over the state machinery of the ancien régime for their own purposes:

Simply put, royal absolutism mightily paved the way for egalitarian mass democracy in the Western civilization by means of putting down and castrating aristocratic power, turning the noblemen into mere high-ranking servants of the crown, or mere glittering but impotent courtiers, instead of the proud and semi-independent feudal warlords they had once been. The crown also considerably curtailed clerical power - and even before the "Enlightened Absolutism" was a thing. Thus it was easy for egalitarian revolutionaries, once they had grabbed control of the centralized state machinery, to continue where the monarchs and despots had left off, considerably accelerating their policies.

The best way to introduce this topic - which boils down to the principle "High & Low against the Middle" - might be this piece written by Roland; IMHO, this is one of the most concisely insightful pieces ever written on the Old Phora, taking inspiration from the theories of Bertrand de Jouvenel:

Petr, I synthesized a theory of the relationship between absolutism and equality from de Jouvenel and other thinkers in the tradition of aristocratic liberalism over at nic's forum. It's clunky and spergish, but I think it captures some of the topics you've been discussing here.

Two terse and contentious definitions:

A notable/noble/aristocrat is a self-sufficient individual with resources adequate for self-sustenance and the physical enforcement of his liberty against others. He is a man of good stock with excellent physical and mental capacities, good character, future-oriented goals, and a relatively loyal and equally robust extended family. Often he is an independent power that exercises authority over a set of consenting individuals, as in autocephalous societies like medieval kingships where a federation of aristocrats is presided over by a "king", or unwilling individuals, as in heterocephalous societies where kingship is imposed exogenously through conquest. Such a man is "free" in the ancient sense of the term.

The masses, in contrast, are individuals who are only self-sufficient to a limited extent and who, if at all, occupy positions of authority with a very limited scope, such as the head of a family. Often they are subject to the authority of the notables. Here we find the early bourgeoisie, the peasants, the proletariat, the serfs and slaves.

With these definitions in place we can assert an equally contentious axiom of human behavior:

Man has a will-to-power such that in every association he will inevitably attempt to maximize his power and aggrandize his person at the expense of others in that association.

Absolutism and equality

Wherever there is a set of nobles and each has relatively equal military and economic resources, there will be a true balance of powers and the tendency toward absolutism will be muted. However, where there is a chance for one noble to compel obedience from the others, there will be conflict, from which the positive relationship between absolutism and equality emerges. The reason for the conflict is clear: the independent authority of the less-powerful nobles represents an obstacle to the imposition of the aspiring absolutist's will.

Historically, the two principle ways for the absolutist to conquer the federation of conquerors are 1) by appealing to the interests of those subjugated by the rival nobles (Caesar), or 2) by conquering foreign peoples and employing them in offices traditionally performed by the other nobles (Alexander). In each case the authority of the exalted is marginalized at the expense of uplifting the unexalted.

The conquest of the conquerors does not signal the end of absolutism's egalitarian march; instead, the absolutist must continue down the hierarchy of independent authorities until there is no longer any impediment to his will. In each case those who are subject to, or enemies of, the authority in question ultimately benefit from absolutism's attack on the authority. Below the rule of the nobility are the religious, ethnic, municipal and familial authorities, all of which present potential obstacles to the absolutist's power, and all of which subjugate a potential class of new allies for the aspiring monarch.

But this trajectory is not followed uniformly to its conclusion in all possible associations. In non-democratic manifestations of absolutism, such as those that obtained in early-modern Europe, the process of equalization is arrested by external and internal restrictions.

External restrictions include the existing effective authorities that remain independent by virtue of their physical distinction from the personality of the absolutist, such as the Church, the nobility and the common people. The physical distinction between the monarch and other authorities magnifies class-consciousness within each authority so that the authority is strengthened vis-a-vis the monarch. Thus we see in the history of absolutism that the triumph over traditional authorities was rarely complete.

Internal restrictions originate from the absolutist himself and include those cosmological and religious principles that govern the scope of an individual's will-to-power as natural law did in the middle ages and Christian common law did in the age of absolutism. In addition to the moral and religious principles that may temper his appetite, economic calculation itself provides an internal restriction on the absolutist, as Hoppe has demonstrated. These restrictions explain the relatively "conservative" and pious dispositions of many monarchs.

Most of the external and internal distinctions are only eliminated with the success of the revolutions against absolutism. Empowered by the egalitarian creations of the absolutist, the masses finally wrest control of the monarch's apparatus for the enforcement of his will – the State – from the monarch himself. Borrowing the legitimacy accumulated by the State over the centuries of its growth, the masses then set about eliminating every opposition to its authority. In the place of the concrete personality of the monarch they set a whole multitude of egos, but the goal of the state remains the same, and its power increases.

No longer the manifestation of a single concrete person but rather the embodiment of the will of everyone under its power, the State is able to eliminate nearly every external restriction on its power. What the absolute monarch failed to do over the course of several centuries is accomplished in a few years by the new "republics."

No longer requiring the legitimacy of divinity to justify the state (for the State is now a creation of the people), the State abandons its commitment to a supernatural origin of law. Divine law is supplanted by positive law, which permits every arbitrary rule to be classified as law and enforced.

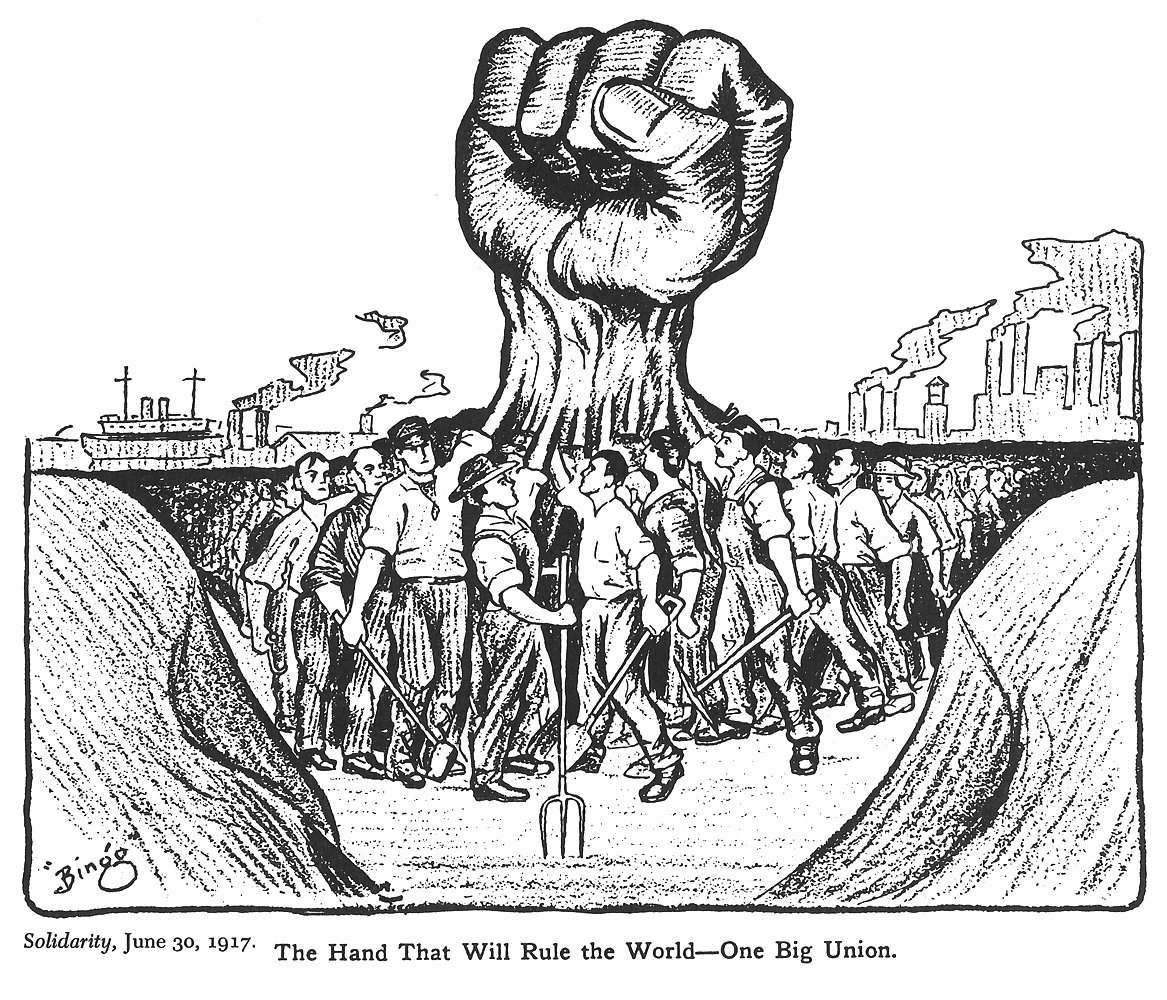

Both of these innovations accelerate the process of equalization so that every time a new aristocracy or elite threatens to emerge, the State quickly allies with those subjugated by the new elite, becoming the ally of workers, minorities, women, etc. Since there are authorities in all spheres of life, the State extends its legislative power to all spheres of society and effectively becomes total.

The great French Revolution was of course a classic example of this phenomenon in action. The Victorian-era writer Charles Kingsley described how the Jacobins took over the state machinery of the ancien régime for their own purposes:

Three Lectures Delivered at the Royal Institution: On the Ancien Régime as ... : Charles Kingsley : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Book digitized by Google from the library of New York Public Library and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

archive.org

[Alexis de Tocqueville] shows, moreover, that the acquiescence in a centralised administration; the expectation that the government should do everything for the people, and nothing for themselves; the consequent loss of local liberties, local peculiarities; the helplessness of the towns and the parishes: and all which issued in making Paris France, and subjecting the whole of a vast country to the arbitrary dictates of a knot of despots in the capital, was not the fruit of the Revolution, but of the Ancien Régime which preceded it; and that Robespierre and his “Comité de Salut Public,” and commissioners sent forth to the four winds of heaven in bonnet rouge and carmagnole complete, to build up and pull down, according to their wicked will, were only handling, somewhat more roughly, the same wires which had been handled for several generations by the Comptroller-General and Council of State, with their provincial intendants.

“Do you know,” said Law to the Marquis d’Argenson, “that this kingdom of France is governed by thirty intendants? You have neither parliament, nor estates, nor governors. It is upon thirty masters of request, despatched into the provinces, that their evil or their good, their fertility or their sterility, entirely depend.”

Last edited: