You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Amish, the Mennonites and the Hutterites

- Thread starter Petr

- Start date

Petr

Administrator

It takes some firm religious faith, not just a momentary fad, to make these kinds of experiments work:

German-speaking Covid denialists seek to build paradise in Paraguay

A group of German, Austrian and Swiss immigrants has implanted an ideologically driven settlement in one of the country’s poorest regions

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

German-speaking Covid denialists seek to build paradise in Paraguay

A group of German, Austrian and Swiss immigrants has implanted an ideologically driven settlement in one of the country’s poorest regions

German-speaking Covid denialists seek to build paradise in Paraguay

The entrance to El Paraíso Verde, 12km from the town of Caazapá. Photograph: William Costa

A group of German, Austrian and Swiss immigrants has implanted an ideologically driven settlement in one of the country’s poorest regions

William Costa in Caazapá

Thu 27 Jan 2022 10.30 GMT

A 1,600-hectare (4,000-acre) gated community, dubbed El Paraíso Verde, or the Green Paradise, is being carved out of the fertile red earth of Caazapá, one of Paraguay’s poorest regions.

The community’s population – consisting mainly of German, Austrian and Swiss immigrants – will eventually swell from 150 to 3,000, according to the owners.

The project’s website bills it as “by far the largest urbanization and settlement project in South America”, describing the colony as a refuge from “socialist trends of current economic and political situations worldwide” – as well as “5G, chemtrails, fluoridated water, mandatory vaccinations and healthcare mandates”.

Immigration to the colony has stepped up since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, with residents interviewed on its YouTube channel attributing their move to scepticism about the virus and vaccines.

Caazapá, a rural region dominated by cattle ranching in the heart of lush eastern Paraguay, saw a jump from four new German residents in 2019 to 101 in 2021, according to official figures. “Anti-vaxxer” immigrants have also been reported settling in other parts of Paraguay.

One German citizen who lives nearby and who does business with Paraíso Verde, cited discredited conspiracy theories about coronavirus vaccines to explain the surge. They claimed that Paraguay’s accommodating immigration laws have proved attractive to Germans who want to “escape the matrix” and flee the “deep state and one world order”.

The entrance to Caazapá regional hospital, which has no ICU beds and only one ambulance. The pandemic has been devastating for the region. Photograph: William Costa

“Many older people are coming. They understand that many people are dying in care homes [after vaccination],” said the German, who asked not to be named. “And the others, in their 40s, are trying to bring their children over here to escape.”

But the appearance of an insular colony of Europeans has been watched with concern by some in the nearby the regional capital, also named Caazapá.

“Why are they here? We don’t know, but we want to find out,” said Rodney Mereles, a former municipal councillor.

On its YouTube channel, Paraíso Verde shares videos describing the pandemic which has killed some 5.5 million people as “non-existent”, promoting false, dangerous Covid “miracle cures”, and advertising Paraguay as a country without pandemic restrictions – despite the government’s clear health protocols.

Even as Paraguay recorded the world’s highest Covid death rate per capita in June 2021, the colony shared videos of large parties in violation of restrictions.

In Germany, sections of society radicalised by the refugee crisis of 2015 have proved a fertile ground for disinformation and conspiracy theories about the pandemic. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland party has tried to revive its waning electoral fortunes by railing against lockdown measures, mask mandates and vaccines.

And a small minority of those sceptics have decided to head abroad, with Bulgaria reported as another popular destination.

The presence in Caazapá of a large group of Covid skeptics worries local health authorities. Dr Nadia Riveros, Caazapá’s head of public health, said the pandemic had been devastating for the region, which has no ICU beds and only one fully equipped ambulance.

“We don’t want to go through that again. I think foreigners, wherever they’re from, should have to get vaccinated before entering the country,” she said.

And as Paraguay faces a quickly escalating third wave of Covid while struggling to improve on the second-lowest vaccination rate in South America, the health ministry announced this month that non-resident foreigners entering the country must now present vaccination certificates.

At least six German nationals without vaccination certificates have been refused entry since this new regulation came into force.

Paraguay has a long and sometimes troubled history of inward-looking immigrant colonies driven by ideological and religious zeal. Settlement projects by Mennonites, Australian socialists and the Unification church among others have all left marks on the country.

European immigrants in the centre of the town of Caazapá. Photograph: William Costa

Paraguay’s most notorious settlement was Nueva Germania, the proto-fascist colony set up in 1886 by Elizabeth Nietzsche – the philosopher’s sister – and her husband Bernhard Förster. Förster died, probably by suicide, as Nueva Germania sank under the weight of financial problems, internal conflict and settlers’ lack of agricultural knowledge.

While Nietzsche and Förster envisioned an Aryan colony untouched by Jewish influence, El Paraíso Verde’s founder and leader Erwin Annau has spoken of preserving Germanic peoples from the presence of Islam and – on a website that was recently taken offline – questioned the blame allocated to Germany for the second world war.

In a 2017 speech given before members of the Paraguayan government, Annau said: “Islam is not part of Germany. We are enlightened Christians, and we are concerned about our daughters. We see the Qur’an as [containing] an ideology of political domination, which is not compatible with democratic and Christian values.”

Paraguay itself has a small but well-established Muslim community in several major cities. Abdun Nur Baten, missionary for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community of Paraguay, highlighted the apparent contradiction in Annau’s comments.

“They say Muslim immigrants don’t integrate, that they don’t adopt German culture or German norms, that they’re not assimilating. So it’s very hypocritical to go to another land and do exactly what you are accusing Muslims of doing: it’s beyond funny how hypocritical it is,” Nur Baten said. He said his community would welcome peaceful dialogue with Paraíso Verde.

But despite concerns in the local community, Paraíso Verde is backed by increasing political and economic power.

The group has frequently met with local and national officials, and claims to have held meetings with Paraguayan health authorities to lobby against tighter Covid regulations.

The entrance to El Paraíso Verde, which is also the base for the community’s company Reljuv, a major local employer. Photograph: William Costa

Gladys Rojas, a former president of Caazapá town council, claimed that Paraíso Verde was protected by links to the political faction of the former Paraguayan president Horacio Cartes. Cartes is a controversial businessman who has repeatedly contested allegations he is linked to cigarette smuggling, but is considered Paraguay’s richest and most powerful person.

Two members of the Cartes family have been board members of Reljuv, a company owned by Paraíso Verde, and in recent municipal elections, the company’s president, Juan Buker, was heavily involved in election campaigns for candidates backed by Cartes.

“They’ve got politicians and money on their side,” said Rojas, adding that many in Caazapá, the region with the highest rate of extreme poverty in Paraguay, were reluctant to ask questions as the colony has become the area’s biggest employer.

Rojas currently faces trespass charges over protests to protect Isla Susu, a nature reserve that experienced heavy environmental damage during construction works at Paraíso Verde. The settlement later paid a fine for the damage.

On a recent afternoon, the Guardian travelled along the dirt road from the town of Caazapá to Paraíso Verde. Close to the long perimeter fence, groups of residents strolled along the track in the slowly softening sun.

At the entrance gate, a Reljuv employee emerged, flanked by guards armed with long guns.

After rejecting the possibility of entry or an interview, the employee aggressively demanded to examine identity documents of all present, even as the reporter attempted to leave.

“You know what to do,” the employee repeated, confusingly. Paraíso Verde did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Last edited:

Petr

Administrator

Bardamu: It is hard for me to express the level of admiration I hold for this: https://gab.com/namelessone11/posts/107718775165071567

Last edited:

Not to promote shitlib "fact checking", but I suspected there was something fishy about that image of the "Amish convoy" accompanying the Gab post and it turns out I was right: https://leadstories.com/hoax-alert/...ch-but-hutterites-did-cook-convoy-dinner.html

Petr

Administrator

Campeche Mennonite Community still resists the Covid-19 vaccine - The Yucatan Times

This group continues to affirm that since there are no cases of Covid-19 in their communities, vaccinations are not necessary. (CAMPECHE - TYT).- While the Vaccination campaign continues to advance in Campehce and that the third booster dose has already started for several population groups...

Campeche Mennonite Community still resists the Covid-19 vaccine

By Yucatan Times on February 14, 2022

(Photo: Yucatan a la mano)

(CAMPECHE – TYT) While the Vaccination campaign continues to advance in Campeche and that the third booster dose has already started for several population groups, there are small communities, among which the Mennonites stand out, who remain skeptical about the anticovid vaccines.

This has been confirmed by health authorities, who although they recognized that only some received the dose, there are those who do not have the first or second injection of any drug, this could also cause a high risk of contagion since it is already very common to see these residents wandering around the city without a mask and without respecting sanitary measures.

So far there are no cases of Covid-19 in the Mennonite camps of El Temporal and Nuevo Progreso, in Campeche, so Mennonites expressed that they do not know if any member of those populations has been infected with coronavirus, and warned that they do not have vaccinated against Covid-19, and they will not do so, according to their uses and customs, and their religion.

Petr

Administrator

This piece, about the Mennonites who settled in the Peruvian Amazon, is an English automatic-translation version of this Spanish-language article:

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/NK3HTCYR2NGCPJYXBUZGZ4OL3I.JPG)

elcomercio.pe

elcomercio.pe

For some, they are the moral reserve of a planet drowned in consumerism. For others, characters suspected of racism, because they avoid mixing with the people of the countries where they live.

They arrived in Peru in 2014, from Bolivia, with the idea of finding new territories where they could lead their lifestyle, oblivious to the inventions of the modern world.

Nevertheless, for four years they have been investigated for the deforestation of large areas of the Amazon in Loreto and Ucayali.

When I visited them for the first time, at the end of 2015, they asked the government for autonomy to educate their children under their Christian standards. The request included exempting their young men from military service. At Mennonite school, children learn to sing and memorize passages from the Bible and, on blackboards with chalk, to master basic mathematics. When they reach puberty, they leave school to dedicate themselves to agricultural and timber production, if they are boys; and to the duties of the home and the field, if they are women.

The Mennonites travel twelve hours by river to market their products in Pucallpa (one of the main ones, fresh cheese). Nor do they employ anyone to cultivate their land. This brought disappointment to the residents, who thought that their arrival would multiply employment.

Thanks to Analí Lavado Agnini and the Cuarto Poder program, I was able to enter two Mennonite colonies in Ucayali and the Huánuco Amazon (the third Mennonite important remains in Father Márquez, in Loreto). That year, the towns of Vanderland and Usterreich looked like recently set up camps, in the middle of large agricultural areas reclaimed from the jungle.

A biblical air blew through those villages built of wood and metal plates, where a child played on stilts and the women sewed in silence. Peace dominated those extensions where the neighbor’s house could be seen five blocks or a kilometer away.

Getting to these towns was not easy, since they were far from Pucallpa and the Mennonites they did not allow the entry of anyone other than local collaborators: truck owners who helped them get their products out.

Mennonite education is the key to its idiosyncrasy or the perpetuity of its traditions. Male and female roles are very different.

Spending a couple of days with them was like witnessing an episode of The Ingalls Family, the 1970s series starring and directed by Michael Landon. And I said it in the report that followed that visit. Only here there was no Laura or Mary Ingalls, but industrious women who only understood the archaic German language that a modern German could not understand.

The Mennonites and the Amish have the same origin, but the former are not as radical as the latter. The followers of Menno Simons accept some technological advances in their daily life, such as tractors and agricultural machinery in general, as well as an extemporaneous type of fuel-powered clothes washers.

Their way of life prevents them from using mechanical vehicles to move around, except when working in the fields. In the photo appears one of the ministers or priests of the community. Everyone in this community carries an immigration card (most have religious immigration status).

They do not tolerate television, radios and much less cell phones. Neither do cars or electricity. His hand-cranked calculators look like something out of a Far West movie.

But, unlike the Amish, they do not isolate themselves from the outside world. They just walk away. They did not accept the covid vaccination because only God could decide on their destinies.

The Mennonites arriving in Peru, they were born in a South American country, and yet only the village chiefs knew how to communicate in broken Spanish. A smaller number of them come from Belize.

Despite the Amazonian heat, they never showed signs of being overwhelmed, buttoned up to their Adam’s apple. The same with them, always sheathed in dresses of simple and dark fabrics.

For all their stoicism and radicalism, these uniformed men in overalls and plaid shirts were kind and sweet.

A quick search on the Internet brings to light dishonorable crimes carried out by a group of them in Manitoba, Bolivia. Young Mennonites they can only form a family with women from the same religious group. Whoever succumbs to the love of any other woman must leave the village.

The modern world and its complex dynamics surround these beings who live under the mandate of a sacred mission, according to them.

An average family at lunch. That day there was chicken broth, fried chicken, fried plantains, and camu camu soda.

This year we visited them again (12 hours by river, from Pucallpa), but for different reasons: the Mennonite colonies of Tierra Blanca in Loreto and Masisea in Ucayali were fined millions of dollars. Christians are supposed to have cut down our primary forests without having the respective permits.

They and their lawyers argue that they are only taking advantage of forests previously exploited by loggers. Satellite images show accelerated forest activity in their domains. The Specialized Prosecutor for Environmental Matters continues to collect information.

A parallel investigation tries to reveal an irregular titling system promoted by state agencies in the properties that today are occupied by the “holy” neighborhoods. Were they cheated by land traffickers?

Similar accusations persecute this group in Mexico and Bolivia. Their children form families, their colonies grow and their fields grow too.

For some, they took the biblical phrase “populate the earth abundantly and multiply in it” to the extreme. For the law, they must reforest the lost paradise.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/NK3HTCYR2NGCPJYXBUZGZ4OL3I.JPG)

Un recorrido por las colonias menonitas en Ucayali y Loreto y su impacto en esas regiones | CRÓNICA

Los menonitas no dejan indiferente a nadie. Hay quienes los quieren, defienden y valoran su estoico apego al trabajo. Y quienes los catalogan de fanáticos y anacrónicos. Ingresamos a las colonias de Ucayali y Loreto. Esta es la historia.

A tour of the Mennonite colonies in Ucayali and Loreto and their impact on those regions

For some, they are the moral reserve of a planet drowned in consumerism. For others, characters suspected of racism, because they avoid mixing with the people of the countries where they live.

They arrived in Peru in 2014, from Bolivia, with the idea of finding new territories where they could lead their lifestyle, oblivious to the inventions of the modern world.

Nevertheless, for four years they have been investigated for the deforestation of large areas of the Amazon in Loreto and Ucayali.

When I visited them for the first time, at the end of 2015, they asked the government for autonomy to educate their children under their Christian standards. The request included exempting their young men from military service. At Mennonite school, children learn to sing and memorize passages from the Bible and, on blackboards with chalk, to master basic mathematics. When they reach puberty, they leave school to dedicate themselves to agricultural and timber production, if they are boys; and to the duties of the home and the field, if they are women.

The Mennonites travel twelve hours by river to market their products in Pucallpa (one of the main ones, fresh cheese). Nor do they employ anyone to cultivate their land. This brought disappointment to the residents, who thought that their arrival would multiply employment.

Thanks to Analí Lavado Agnini and the Cuarto Poder program, I was able to enter two Mennonite colonies in Ucayali and the Huánuco Amazon (the third Mennonite important remains in Father Márquez, in Loreto). That year, the towns of Vanderland and Usterreich looked like recently set up camps, in the middle of large agricultural areas reclaimed from the jungle.

A biblical air blew through those villages built of wood and metal plates, where a child played on stilts and the women sewed in silence. Peace dominated those extensions where the neighbor’s house could be seen five blocks or a kilometer away.

Getting to these towns was not easy, since they were far from Pucallpa and the Mennonites they did not allow the entry of anyone other than local collaborators: truck owners who helped them get their products out.

Mennonite education is the key to its idiosyncrasy or the perpetuity of its traditions. Male and female roles are very different.

Spending a couple of days with them was like witnessing an episode of The Ingalls Family, the 1970s series starring and directed by Michael Landon. And I said it in the report that followed that visit. Only here there was no Laura or Mary Ingalls, but industrious women who only understood the archaic German language that a modern German could not understand.

The Mennonites and the Amish have the same origin, but the former are not as radical as the latter. The followers of Menno Simons accept some technological advances in their daily life, such as tractors and agricultural machinery in general, as well as an extemporaneous type of fuel-powered clothes washers.

Their way of life prevents them from using mechanical vehicles to move around, except when working in the fields. In the photo appears one of the ministers or priests of the community. Everyone in this community carries an immigration card (most have religious immigration status).

They do not tolerate television, radios and much less cell phones. Neither do cars or electricity. His hand-cranked calculators look like something out of a Far West movie.

But, unlike the Amish, they do not isolate themselves from the outside world. They just walk away. They did not accept the covid vaccination because only God could decide on their destinies.

The Mennonites arriving in Peru, they were born in a South American country, and yet only the village chiefs knew how to communicate in broken Spanish. A smaller number of them come from Belize.

Despite the Amazonian heat, they never showed signs of being overwhelmed, buttoned up to their Adam’s apple. The same with them, always sheathed in dresses of simple and dark fabrics.

For all their stoicism and radicalism, these uniformed men in overalls and plaid shirts were kind and sweet.

A quick search on the Internet brings to light dishonorable crimes carried out by a group of them in Manitoba, Bolivia. Young Mennonites they can only form a family with women from the same religious group. Whoever succumbs to the love of any other woman must leave the village.

The modern world and its complex dynamics surround these beings who live under the mandate of a sacred mission, according to them.

An average family at lunch. That day there was chicken broth, fried chicken, fried plantains, and camu camu soda.

This year we visited them again (12 hours by river, from Pucallpa), but for different reasons: the Mennonite colonies of Tierra Blanca in Loreto and Masisea in Ucayali were fined millions of dollars. Christians are supposed to have cut down our primary forests without having the respective permits.

They and their lawyers argue that they are only taking advantage of forests previously exploited by loggers. Satellite images show accelerated forest activity in their domains. The Specialized Prosecutor for Environmental Matters continues to collect information.

A parallel investigation tries to reveal an irregular titling system promoted by state agencies in the properties that today are occupied by the “holy” neighborhoods. Were they cheated by land traffickers?

Similar accusations persecute this group in Mexico and Bolivia. Their children form families, their colonies grow and their fields grow too.

For some, they took the biblical phrase “populate the earth abundantly and multiply in it” to the extreme. For the law, they must reforest the lost paradise.

Petr

Administrator

The question of ethnic dominance can touch even such quaint issues as ostrich farming - some people in Belize feel their country is already too dependent on the Mennonites for the food production (and on the Chinese as merchant middlemen):

Diverging Views on Mennonites And Ostriches

June 1, 2022

And last night, you heard the BAHA chairman, Hugh O'Brien, say that he doesn't think the Mennonite community should get into the ostrich industry, considering that they monopolise the poultry and dairy industries. While Marin agreed with him, the minister isn't too keen on leaving any farmer behind.

Hon. Kareem Musa, Minister of Home Affairs & New Growth Industries

Hon. Kareem Musa, Minister of Home Affairs & New Growth Industries

"We are an open and free market and so any group of people, any farmer that's interest in this particular industry can explore and venture and invest in this industry. There's no restriction on who can invest in it, I think what we have to look at is not giving any particular group any incentives or additional concession more than others, it has to be across the board opportunities for all Belizeans, not just a specific group."

Nancy Marin, Ostrich Farmer

"I was also happy to note, I saw you guys interview Mr O'Brien, the new chairman for BAHA, he is fully onboard and I was very happy for his last statement requesting that the Mennonites step back off of this industry because my fight for seven years was not just to bring an animal into Belize, or a new species into Belize. My fight is that the farmer of Belize have been left out, we have given up our food sovereignty to the Mennonites and with groceries to the Chinese, but in this case we're focusing on the Mennonites and it is time that local farmers have something for ourselves and this is ostrich."

Courtney Menzies:

"How difficult is it to rear ostriches and do you feel like Belizeans will make the effort, Belizean farmers?"

Nancy Marin, Ostrich Farmer

"You know, I grew up in a cattle ranch so I'm used to livestock, and I will tell you that it is a lot easier, it is a lot easier than rearing cows. So I have gotten interest, we have at least 16 local farmers that are interested, people are texting, saying, I have ten acres, I have fifty acres, how many ostriches could I rear with this amount of land. We can actually rear are ostriches than we can livestock in the amount of land small farmers have. So it's going to be very easy as long as we follow procedures and we keep the health and sanitary confinement of the animals is what is important but as long as we get through that, it will be easy. I think we will have management plan that will be very easy for farmers to follow and we will follow all of the procedures and requirements that both BAHA and Forestry have to give us but we will do that under a very organised structure, we are forming the Association of Ostrich Livestock in Belize."

And according to Marin, the association will be the only organisation that will be allowed to buy ostriches, meaning that individual farmers - or even residents - won't be able to purchase them on their own.

Diverging Views on Mennonites And Ostriches

June 1, 2022

And last night, you heard the BAHA chairman, Hugh O'Brien, say that he doesn't think the Mennonite community should get into the ostrich industry, considering that they monopolise the poultry and dairy industries. While Marin agreed with him, the minister isn't too keen on leaving any farmer behind.

"We are an open and free market and so any group of people, any farmer that's interest in this particular industry can explore and venture and invest in this industry. There's no restriction on who can invest in it, I think what we have to look at is not giving any particular group any incentives or additional concession more than others, it has to be across the board opportunities for all Belizeans, not just a specific group."

Nancy Marin, Ostrich Farmer

"I was also happy to note, I saw you guys interview Mr O'Brien, the new chairman for BAHA, he is fully onboard and I was very happy for his last statement requesting that the Mennonites step back off of this industry because my fight for seven years was not just to bring an animal into Belize, or a new species into Belize. My fight is that the farmer of Belize have been left out, we have given up our food sovereignty to the Mennonites and with groceries to the Chinese, but in this case we're focusing on the Mennonites and it is time that local farmers have something for ourselves and this is ostrich."

Courtney Menzies:

"How difficult is it to rear ostriches and do you feel like Belizeans will make the effort, Belizean farmers?"

Nancy Marin, Ostrich Farmer

"You know, I grew up in a cattle ranch so I'm used to livestock, and I will tell you that it is a lot easier, it is a lot easier than rearing cows. So I have gotten interest, we have at least 16 local farmers that are interested, people are texting, saying, I have ten acres, I have fifty acres, how many ostriches could I rear with this amount of land. We can actually rear are ostriches than we can livestock in the amount of land small farmers have. So it's going to be very easy as long as we follow procedures and we keep the health and sanitary confinement of the animals is what is important but as long as we get through that, it will be easy. I think we will have management plan that will be very easy for farmers to follow and we will follow all of the procedures and requirements that both BAHA and Forestry have to give us but we will do that under a very organised structure, we are forming the Association of Ostrich Livestock in Belize."

And according to Marin, the association will be the only organisation that will be allowed to buy ostriches, meaning that individual farmers - or even residents - won't be able to purchase them on their own.

Last edited:

Petr

Administrator

It seems that the globo-media makes these kind of attack pieces on the Mennonites on a regular basis:

www.reuters.com

www.reuters.com

Visuals by Jose Luis Gonzalez

Reporting by Cassandra Garrison

Filed: July 12, 2022, 12 p.m. GMT

The largest tropical forest in North America yields to perfect rows of corn and soy. Light-haired women with blue eyes in wide-brimmed hats bump down a dirt road in a horse and buggy, past simple brick homes and a whitewashed schoolhouse: A Mennonite community in southern Mexico.

Here, in the state of Campeche on the Yucatan Peninsula at the northern edge of the Maya Forest, the Mennonites say they live to traditional pacifist values and that expanding farms to provide a simple life for their families is the will of God.

In the eyes of ecologists and now the Mexican government, which once welcomed their agricultural prowess, the Mennonites' ranches are an environmental disaster rapidly razing the jungle, one of the continent's biggest carbon sinks and a home to endangered jaguars.

Juan Neudorf throws a rope towards his horses in the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico, April 28, 2021. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Smaller only than the Amazon, the Maya Forest is shrinking annually by an area the size of Dallas, according to Global Forest Watch, a non-profit organisation that monitors deforestation.

The government of President Andres Manuel Lopez is now pressuring the Mennonites to shift to more sustainable practices, but despite a deal between some Mennonite settlements and the government, ongoing land clearance was visible in two villages visited by Reuters in February and May.

A young man cuts tree branches in the Mennonite community of Chavi, Hecelchakan, Campeche state, Mexico, May 11, 2022. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Farmers such as Isaak Dyck Thiessen, a leader in the Mennonite settlement of Chavi, are finding it hard to adjust.

"Our people just want to be left in peace," he said, standing on a shaded doorstep to escape the unforgiving afternoon sun. Beyond his neat farm rose the green wall of the rainforest.

In search of land and isolation, Mennonites – for whom agricultural toil is a core tenet of their Christian faith – grew in numbers and expanded into remote parts of Mexico after first arriving from Canada in the early 20th Century.

Despite shunning electricity and other modern amenities away from work, their farming has evolved to include bulldozers and chainsaws as well as tractors and harvesters.

In Campeche, where Mennonites arrived in the 1980s, around 8,000 sq km of forest, nearly a fifth of the state's tree cover, has been lost in the last 20 years, with 2020 the worst on record, according to Global Forest Watch.

Groups including palm oil farmers and cattle ranchers also engage in widespread land clearance. Data on how much deforestation is driven by Mennonite settlers and how much by other groups is not readily available.

One 2017 study, led by Mexico's Universidad Veracruzana, found that property owned by Mennonites in Campeche had rates of deforestation four times higher than non-Mennonite properties.

The clearance contrasts with the traditions of indigenous farmers who have rotated corn and harvested forest products such as honey and natural rubber since Maya cities dominated the jungle from the Yucatan to El Salvador.

Itself under international pressure to pursue a greener agenda, in August the government persuaded some Campeche Mennonite settlements to sign an agreement to stop deforesting land.

Not all the communities signed up.

FIRE AND SAWS

On the edge of the remote village of Valle Nuevo, Reuters journalists witnessed farmers clearing jungle and setting fires to prepare for planting.

Jacob Harder, Jr., a Mennonite school teacher in Valle Nuevo said the agreement had not made an impact on how Valle Nuevo approaches agriculture.

"We haven't changed anything," Harder said.

Leader Dyck Thiessen and a lawyer representing some communities and farmers said Mennonites, who take a pacifist approach to conflict, felt attacked and scapegoated by the government's efforts.

Jose Uriel Reyna Tecua, the lawyer, said they were unfairly blamed while the government pays less attention to others that deforest.

Enrique Friesen, 17, (R) carries a plastic bag of sorghum for quality testing before his family's harvest is sold, in the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico, February 28, 2022. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

At one meeting last year, Agustin Avila, a senior official at the federal environment ministry, warned villagers the military could be brought to the area to prevent deforestation if the communities did not change their ways, Reyna Tecua said.

"That was the direct threat," Reyna Tecua said.

In response to a Reuters question about Avila's alleged comments, the environment ministry denied any mention of using the military, saying the government operated on the basis of dialogue.

Carlos Tucuch, head of the Campeche office of Mexico's National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR), told Reuters the government was not singling out the Mennonites and was also working to tackle other causes of deforestation.

THE MOVE SOUTH

Mennonites trace their roots to a group of Christian radicals in 16th century Germany and surrounding areas that emerged in opposition to both Roman Catholic doctrine and mainstream Protestant faiths during the Reformation.

In the 1920s, a group of about 6,000 moved to northern Mexico and established themselves as important crop producers.

Still speaking Plautdietsch - a blend of Low German, Prussian dialects and Dutch - a few thousand moved to the forests of Campeche in the 1980s. They bought and leased tracts of jungle, some from local Maya indigenous communities. More arrived in recent years as climate change worsened drought in the north.

In 1992, legislation made it easier to develop, rent or sell previously protected forest, increasing deforestation and the number of farms in the state.

When Mexico opened up the use of genetically modified soy in the 2000s, Mennonites in Campeche embraced the crop and the use of the glyphosate weedkiller Roundup, designed to work alongside GMO crops, according to Edward Ellis, a researcher at Universidad Veracruzana.

The higher yields means more income to support large families - 10 children is not unusual - and live a simple life supported by the land, said historian Royden Loewen, explaining that settlements often invest as much as 90% of profits to buy land.

At least five Mennonites who spoke to Reuters said they wanted to acquire more land for their families.

While most Mexican Mennonites remain in the north, there are now between 14,000 and 15,000 in Campeche spread over about 20 settlements.

"If God grants you, then you grow," said Dyck Thiessen, who has attended government meetings but did not sign the agreement.

FOREST TOLL

The Mennonites largely maintain a tense peace with local indigenous communities who serve as guardians to the surrounding forest but also rent equipment from their new neighbors for their own land.

"With them, we began to have access to machinery. We see that it gives us results," said Wilfredo Chicav, 56, a Maya farmer.

Such advances in agricultural efficiency has taken its toll on the Maya Forest, home to fauna that includes up to 400 species of birds.

Its 100 species of mammal include the jaguar, at risk of extinction in Mexico if its habitat shrinks, said the forestry commission's Tucuch.

Between 2001 and 2018, the three states that comprise the forest in Mexico lost about 15,000 sq km of tree cover, an area that would cover much of El Salvador.

This is driving a shorter rainy season. Farmers used to schedule planting for the first of May, now they often wait until July as less forest implies less rainfall capture, leading to a drop in moisture uptake in the air and a decrease in rain, Tucuch said.

Campeche's Environment Secretary, Sandra Laffon, said the Mennonites in the state did not always have the right paperwork to turn the forest into farmland.

Reyna Tecua acknowledged problems with land purchases. Families sometimes fall victim to deals based on a handshake and verbal word, and sellers can take advantage by promising land that is not up for legal sale in the first place, he said.

The agreement signed last year created a permanent working group between the government and Mennonite communities to try to resolve permitting, land ownership and administrative and criminal complaints against them from local people including for illegal logging.

Laffon said there were signs the agreement is having an impact. Global Forest Watch data showed a decrease in deforestation in Campeche in 2021, but said that could be the result of factors including a lack of remaining land suitable for agriculture and government incentive programs, which include a nationwide scheme popular with Maya indigenous farmers that rewards tree planting.

The Harder family pray before having breakfast, after they moved from the Mennonite community of El Sabinal, Chihuahua, to the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico April 29, 2021. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Mennonite leaders are seeking a proposal from the government that won't cut their production dramatically, Reyna Tecua said. A government plan to phase out glyphosate by 2024 is the biggest worry for many, he said.

However, Leal said lower production may be a price farmers, including Mennonites, have to pay to protect the environment, Laffon said.

"We are at the point of having to sacrifice our position" as Mexico's second largest grain producer "for a healthier Campeche," she said.

Lifting his cap to wipe sweat from his brow, Dyck Thiessen, the Mennonite leader, doubted organic methods proposed by the government would be successful. Tension with officials has stalled his plans to acquire more land, he said.

Still, he has faith.

"If the government shuts us down," he says, "God will open for us."

God's will or ecological disaster? Mennonite deforestation in Mexico

The largest tropical forest in North America yields to perfect rows of corn and soy. Light-haired women with blue eyes in wide-brimmed hats bump down a dirt road in a horse and buggy, past simple brick homes and a whitewashed schoolhouse: A Mennonite community in southern Mexico.

God's will or ecological disaster? Mexico takes aim at Mennonite deforestation

Visuals by Jose Luis Gonzalez

Reporting by Cassandra Garrison

Filed: July 12, 2022, 12 p.m. GMT

The largest tropical forest in North America yields to perfect rows of corn and soy. Light-haired women with blue eyes in wide-brimmed hats bump down a dirt road in a horse and buggy, past simple brick homes and a whitewashed schoolhouse: A Mennonite community in southern Mexico.

Here, in the state of Campeche on the Yucatan Peninsula at the northern edge of the Maya Forest, the Mennonites say they live to traditional pacifist values and that expanding farms to provide a simple life for their families is the will of God.

In the eyes of ecologists and now the Mexican government, which once welcomed their agricultural prowess, the Mennonites' ranches are an environmental disaster rapidly razing the jungle, one of the continent's biggest carbon sinks and a home to endangered jaguars.

Juan Neudorf throws a rope towards his horses in the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico, April 28, 2021. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Smaller only than the Amazon, the Maya Forest is shrinking annually by an area the size of Dallas, according to Global Forest Watch, a non-profit organisation that monitors deforestation.

The government of President Andres Manuel Lopez is now pressuring the Mennonites to shift to more sustainable practices, but despite a deal between some Mennonite settlements and the government, ongoing land clearance was visible in two villages visited by Reuters in February and May.

A young man cuts tree branches in the Mennonite community of Chavi, Hecelchakan, Campeche state, Mexico, May 11, 2022. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Farmers such as Isaak Dyck Thiessen, a leader in the Mennonite settlement of Chavi, are finding it hard to adjust.

"Our people just want to be left in peace," he said, standing on a shaded doorstep to escape the unforgiving afternoon sun. Beyond his neat farm rose the green wall of the rainforest.

In search of land and isolation, Mennonites – for whom agricultural toil is a core tenet of their Christian faith – grew in numbers and expanded into remote parts of Mexico after first arriving from Canada in the early 20th Century.

Despite shunning electricity and other modern amenities away from work, their farming has evolved to include bulldozers and chainsaws as well as tractors and harvesters.

In Campeche, where Mennonites arrived in the 1980s, around 8,000 sq km of forest, nearly a fifth of the state's tree cover, has been lost in the last 20 years, with 2020 the worst on record, according to Global Forest Watch.

Groups including palm oil farmers and cattle ranchers also engage in widespread land clearance. Data on how much deforestation is driven by Mennonite settlers and how much by other groups is not readily available.

One 2017 study, led by Mexico's Universidad Veracruzana, found that property owned by Mennonites in Campeche had rates of deforestation four times higher than non-Mennonite properties.

The clearance contrasts with the traditions of indigenous farmers who have rotated corn and harvested forest products such as honey and natural rubber since Maya cities dominated the jungle from the Yucatan to El Salvador.

Itself under international pressure to pursue a greener agenda, in August the government persuaded some Campeche Mennonite settlements to sign an agreement to stop deforesting land.

Not all the communities signed up.

FIRE AND SAWS

On the edge of the remote village of Valle Nuevo, Reuters journalists witnessed farmers clearing jungle and setting fires to prepare for planting.

Jacob Harder, Jr., a Mennonite school teacher in Valle Nuevo said the agreement had not made an impact on how Valle Nuevo approaches agriculture.

"We haven't changed anything," Harder said.

Leader Dyck Thiessen and a lawyer representing some communities and farmers said Mennonites, who take a pacifist approach to conflict, felt attacked and scapegoated by the government's efforts.

Jose Uriel Reyna Tecua, the lawyer, said they were unfairly blamed while the government pays less attention to others that deforest.

Enrique Friesen, 17, (R) carries a plastic bag of sorghum for quality testing before his family's harvest is sold, in the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico, February 28, 2022. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

At one meeting last year, Agustin Avila, a senior official at the federal environment ministry, warned villagers the military could be brought to the area to prevent deforestation if the communities did not change their ways, Reyna Tecua said.

"That was the direct threat," Reyna Tecua said.

In response to a Reuters question about Avila's alleged comments, the environment ministry denied any mention of using the military, saying the government operated on the basis of dialogue.

Carlos Tucuch, head of the Campeche office of Mexico's National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR), told Reuters the government was not singling out the Mennonites and was also working to tackle other causes of deforestation.

THE MOVE SOUTH

Mennonites trace their roots to a group of Christian radicals in 16th century Germany and surrounding areas that emerged in opposition to both Roman Catholic doctrine and mainstream Protestant faiths during the Reformation.

In the 1920s, a group of about 6,000 moved to northern Mexico and established themselves as important crop producers.

Still speaking Plautdietsch - a blend of Low German, Prussian dialects and Dutch - a few thousand moved to the forests of Campeche in the 1980s. They bought and leased tracts of jungle, some from local Maya indigenous communities. More arrived in recent years as climate change worsened drought in the north.

In 1992, legislation made it easier to develop, rent or sell previously protected forest, increasing deforestation and the number of farms in the state.

When Mexico opened up the use of genetically modified soy in the 2000s, Mennonites in Campeche embraced the crop and the use of the glyphosate weedkiller Roundup, designed to work alongside GMO crops, according to Edward Ellis, a researcher at Universidad Veracruzana.

The higher yields means more income to support large families - 10 children is not unusual - and live a simple life supported by the land, said historian Royden Loewen, explaining that settlements often invest as much as 90% of profits to buy land.

At least five Mennonites who spoke to Reuters said they wanted to acquire more land for their families.

While most Mexican Mennonites remain in the north, there are now between 14,000 and 15,000 in Campeche spread over about 20 settlements.

"If God grants you, then you grow," said Dyck Thiessen, who has attended government meetings but did not sign the agreement.

FOREST TOLL

The Mennonites largely maintain a tense peace with local indigenous communities who serve as guardians to the surrounding forest but also rent equipment from their new neighbors for their own land.

"With them, we began to have access to machinery. We see that it gives us results," said Wilfredo Chicav, 56, a Maya farmer.

Such advances in agricultural efficiency has taken its toll on the Maya Forest, home to fauna that includes up to 400 species of birds.

Its 100 species of mammal include the jaguar, at risk of extinction in Mexico if its habitat shrinks, said the forestry commission's Tucuch.

Between 2001 and 2018, the three states that comprise the forest in Mexico lost about 15,000 sq km of tree cover, an area that would cover much of El Salvador.

This is driving a shorter rainy season. Farmers used to schedule planting for the first of May, now they often wait until July as less forest implies less rainfall capture, leading to a drop in moisture uptake in the air and a decrease in rain, Tucuch said.

Campeche's Environment Secretary, Sandra Laffon, said the Mennonites in the state did not always have the right paperwork to turn the forest into farmland.

Reyna Tecua acknowledged problems with land purchases. Families sometimes fall victim to deals based on a handshake and verbal word, and sellers can take advantage by promising land that is not up for legal sale in the first place, he said.

The agreement signed last year created a permanent working group between the government and Mennonite communities to try to resolve permitting, land ownership and administrative and criminal complaints against them from local people including for illegal logging.

Laffon said there were signs the agreement is having an impact. Global Forest Watch data showed a decrease in deforestation in Campeche in 2021, but said that could be the result of factors including a lack of remaining land suitable for agriculture and government incentive programs, which include a nationwide scheme popular with Maya indigenous farmers that rewards tree planting.

The Harder family pray before having breakfast, after they moved from the Mennonite community of El Sabinal, Chihuahua, to the Mennonite community of Valle Nuevo, Campeche state, Mexico April 29, 2021. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez.

Mennonite leaders are seeking a proposal from the government that won't cut their production dramatically, Reyna Tecua said. A government plan to phase out glyphosate by 2024 is the biggest worry for many, he said.

However, Leal said lower production may be a price farmers, including Mennonites, have to pay to protect the environment, Laffon said.

"We are at the point of having to sacrifice our position" as Mexico's second largest grain producer "for a healthier Campeche," she said.

Lifting his cap to wipe sweat from his brow, Dyck Thiessen, the Mennonite leader, doubted organic methods proposed by the government would be successful. Tension with officials has stalled his plans to acquire more land, he said.

Still, he has faith.

"If the government shuts us down," he says, "God will open for us."

Petr

Administrator

A dry but detailed academic article:

Figure 2. Map of Latin America Mennonite colonies.

Pious pioneers: the expansion of Mennonite colonies in Latin America

Nearly one hundred years ago, a group of Mennonites left the prairies of Manitoba for the deserts of Northern Mexico. Since then, Mennonites have created over two hundred agricultural colonies acro...

www.tandfonline.com

Before we proceed, a few words about the nature of these colonies are in order. Mennonite colonies in Latin America are distinct from other settlements in their morphology and organization. Centered around a church and school, they typically take the form of one or several ‘street-villages’ or Straßendörfer, consisting of a row of farmhouses evenly spaced on either side of a road, each housing one family (Figure 4). Life revolves around mixed farming, the main livelihood for the large majority of the Mennonite population. Each village is headed by an elected leader called Dorfschulze (Village leader) who manages local affairs, while the colony is represented by one or more Vorsteher (Colony leader). Religious leaders called Prediger, Diakone, and Ältester (Preacher, Deacon, and Elder or Bishop), elected for life, exert important influence on colony affairs. Small colonies may have as few as a dozen families organized along a single village, while larger colonies can reach several thousands of individuals in dozens of villages, with multiple schools, churches, and Vorsteher. Numerous colonies reject some modern technologies, which are seen as corrupting influences. The most conservative colonies reject the use of rubber tires on tractors and of telephones and the connection of houses to the electricity grid, among other things. Members of more progressive colonies find it normal to own smartphones or pick-up trucks and have TV. Diversity does not stop at technology adoption: colonies (and sometimes, villages within colonies) further differ in their positions towards education, labour, language, and more generally, relationships to the outside world.

Figure 2. Map of Latin America Mennonite colonies.

Petr

Administrator

Yet another Mennonite-bashing article from the Guardian:

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

Mennonite men in Wanderland, Loreto region, in the Peruvian Amazon. Photograph: Dan Collyns/The Guardian

Dan Collyns in Wanderland

Sun 11 Sep 2022 00.00 BST

Were it not for the ebullient fecundity of the Amazon rainforest surrounding it, Wanderland could almost be a stretch of Dutch farmland from the 19th century; a straight muddy track bisects rows of neatly spaced farmyards with perpendicular houses and barns.

A typical morning begins as horse-drawn buggies driven by smiling blond-haired, blue-eyed boys collect shiny churns of fresh milk from farm gates to be made into cheese. The name given to this pastoral idyll carved out of thick foliage of the jungle seems to need little translation, even from Plautdietsch, the mixture of Low German and Dutch spoken by its inhabitants.

But there is unease in this rustic paradise. It is one of three Mennonite communities being investigated by Peruvian prosecutors over accusations of illegally deforesting more than 3,440 hectares (34 sq km) of tropical rainforest in the past five years. The brush with the law has alarmed the community of about 100 families who fear they could lose the land which they have made their home.

...

Mennonite boys carry out chores on the farm from a young age. By the age of 13 they are working full-time. Photograph: The Guardian

...

The remote tract of jungle suited the Mennonites’ preference for being left alone. The Guardian travelled for 14 hours by boat down the Ucayali river and drove for another hour along a muddy track to visit the community which sits about halfway between Pucallpa and Iquitos, the largest city in the world accessible only by boat or plane.

The nearest settlement to the new Mennonite colonies, Tierra Blanca, is a poor riverside outpost which suffers occasional outbursts of violence as it sits on a cocaine trafficking route. There the local people welcome the dungaree-clad settlers and the womenfolk in long cape dresses with curious amusement. Old-timers say decades of logging has stripped any valuable tropical hardwoods from the forest where the communities now live.

“It was secondary [forest] because the loggers had already used all the wood,” said Thiesen. “We don’t work wood. We prefer the soil, to work the land, he added, although he admitted the leftover timber was used to build “houses, schools, churches, bridges, some little things”.

Legally, it is an important distinction. Secondary forest is one step closer to purma, the scrub which grows after tree felling. Purma can be legally transitioned to agricultural use while felling primary rainforest is illegal.

Matt Finer, a senior research specialist at NGO Amazon Conservation, disagrees with Thiesen’s assertion. “The area was selectively logged, as is much of the Amazon but it’s still primary forest,” he said.

Mennonite settlements had become the “new leading cause of large-scale deforestation in Peru”, he said. “In total, we have now documented the deforestation of 3,968 hectares across four new colonies established in the Peruvian Amazon since 2017,” he added. Three out of those four colonies are in Tierra Blanca.

Environmentalists worry this could just be the beginning of the Mennonite invasion in Peru. Satellite images show land clearing for another settlement, also in Loreto, a vast Amazon region the size of Germany. A 2021 study in the Journal of Land Use Science says Mennonites have 200 settlements across seven countries in Latin America and collectively occupy more land than the Netherlands.

Peru lost a record 2,032 sq km of Amazon to deforestation in 2020, a figure almost four times the 548 sq km it lost in 2019, according to its environment ministry.

The Mennonites may be easy targets for environmental prosecutors but their neighbours have jumped to their defence.

“The Mennonite colony has changed the face of this village,” said Medelú Saldaña, the former mayor of Tierra Blanca. “We are blessed to be able to learn from this orderly agriculture.”

The Mennonites sell their cheese and other dairy products locally and as experts in growing soya, sorghum and rice, their farming knowhow is valued by the locals.

“[They] have come to invigorate the economy of our district, where the state neither makes an appearance nor invests,” Saldaña added.

Prohibited by their beliefs from using modern technology, the Christian group do not drive any vehicles except for tractors so they rely on local transportation for journeys to and from their communities, as well as longer journeys by river to sell their products at market.

The Mennonites being accused of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon

A brush with the law has alarmed the community of about 100 families who fear losing the land they have made their home

The Mennonites being accused of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon

Mennonite men in Wanderland, Loreto region, in the Peruvian Amazon. Photograph: Dan Collyns/The Guardian

Dan Collyns in Wanderland

Sun 11 Sep 2022 00.00 BST

Were it not for the ebullient fecundity of the Amazon rainforest surrounding it, Wanderland could almost be a stretch of Dutch farmland from the 19th century; a straight muddy track bisects rows of neatly spaced farmyards with perpendicular houses and barns.

A typical morning begins as horse-drawn buggies driven by smiling blond-haired, blue-eyed boys collect shiny churns of fresh milk from farm gates to be made into cheese. The name given to this pastoral idyll carved out of thick foliage of the jungle seems to need little translation, even from Plautdietsch, the mixture of Low German and Dutch spoken by its inhabitants.

But there is unease in this rustic paradise. It is one of three Mennonite communities being investigated by Peruvian prosecutors over accusations of illegally deforesting more than 3,440 hectares (34 sq km) of tropical rainforest in the past five years. The brush with the law has alarmed the community of about 100 families who fear they could lose the land which they have made their home.

...

Mennonite boys carry out chores on the farm from a young age. By the age of 13 they are working full-time. Photograph: The Guardian

...

The remote tract of jungle suited the Mennonites’ preference for being left alone. The Guardian travelled for 14 hours by boat down the Ucayali river and drove for another hour along a muddy track to visit the community which sits about halfway between Pucallpa and Iquitos, the largest city in the world accessible only by boat or plane.

The nearest settlement to the new Mennonite colonies, Tierra Blanca, is a poor riverside outpost which suffers occasional outbursts of violence as it sits on a cocaine trafficking route. There the local people welcome the dungaree-clad settlers and the womenfolk in long cape dresses with curious amusement. Old-timers say decades of logging has stripped any valuable tropical hardwoods from the forest where the communities now live.

“It was secondary [forest] because the loggers had already used all the wood,” said Thiesen. “We don’t work wood. We prefer the soil, to work the land, he added, although he admitted the leftover timber was used to build “houses, schools, churches, bridges, some little things”.

Legally, it is an important distinction. Secondary forest is one step closer to purma, the scrub which grows after tree felling. Purma can be legally transitioned to agricultural use while felling primary rainforest is illegal.

Matt Finer, a senior research specialist at NGO Amazon Conservation, disagrees with Thiesen’s assertion. “The area was selectively logged, as is much of the Amazon but it’s still primary forest,” he said.

Mennonite settlements had become the “new leading cause of large-scale deforestation in Peru”, he said. “In total, we have now documented the deforestation of 3,968 hectares across four new colonies established in the Peruvian Amazon since 2017,” he added. Three out of those four colonies are in Tierra Blanca.

Environmentalists worry this could just be the beginning of the Mennonite invasion in Peru. Satellite images show land clearing for another settlement, also in Loreto, a vast Amazon region the size of Germany. A 2021 study in the Journal of Land Use Science says Mennonites have 200 settlements across seven countries in Latin America and collectively occupy more land than the Netherlands.

Peru lost a record 2,032 sq km of Amazon to deforestation in 2020, a figure almost four times the 548 sq km it lost in 2019, according to its environment ministry.

The Mennonites may be easy targets for environmental prosecutors but their neighbours have jumped to their defence.

“The Mennonite colony has changed the face of this village,” said Medelú Saldaña, the former mayor of Tierra Blanca. “We are blessed to be able to learn from this orderly agriculture.”

The Mennonites sell their cheese and other dairy products locally and as experts in growing soya, sorghum and rice, their farming knowhow is valued by the locals.

“[They] have come to invigorate the economy of our district, where the state neither makes an appearance nor invests,” Saldaña added.

Prohibited by their beliefs from using modern technology, the Christian group do not drive any vehicles except for tractors so they rely on local transportation for journeys to and from their communities, as well as longer journeys by river to sell their products at market.

Macrobius

Megaphoron

Plenty of Amish and Mennonites in Indiana. My maternal family (not either sect) is from Porter Co. in the NW part of the State, and I lived for many years in Bloomington, downstate not far from Beanblossom

orangebeanindiana.com

orangebeanindiana.com

Indiana’s Amish & Mennonite Communities - OrangeBean Indiana

By Mary Giorgio Indiana is home to thousands of Amish and Mennonite residents. People tend to confuse the two groups because they share many similarities. However, Amish and Mennonites are distinct groups that practice their religious traditions in unique ways. Both Amish and Mennonite religions...

orangebeanindiana.com

orangebeanindiana.com

Petr

Administrator

Excavations at Maya Settlement in Belize Tell Story of Maya Golden Age

Representatives of the Belize Institute of Archaeology have been working with graduate students from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign on a series of excavations in Central America.

UPDATED 13 SEPTEMBER, 2022 - 22:57

NATHAN FALDE

Excavations at Maya Settlement in Belize Tell Story of Maya Golden Age

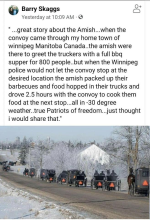

Representatives of the Belize Institute of Archaeology have been working with graduate students from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign on a series of excavations in Central America. During a recent dig, the team of established and aspiring scholars was delighted to find a shallowly buried ancient Maya settlement, on a site that had long ago been converted into an agricultural field by a Mennonite farming community.

At the Spanish Lookout Mennonite community in Central Belize, the archaeologists and graduate students were given access to a large, open, heavily plowed field. They knew this was the perfect place to look for an ancient Maya settlement, since the upper part of the settlement ruins could be seen by the naked eye.

“White mounds, the remnants of these houses, pock the landscape as far as the eye can see, a stark reminder of what existed more than 1,000 years ago,” anthropology graduate students Rachel Gill and Yifan Wang wrote in a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign press release announcing the unearthing of the Maya settlement in Belize. The white mounds were easily visible in aerial photographs, which are often used by archaeologists looking for hidden ruins to excavate.

Anthropology graduate students Rachel Gill and Yifan Wang are studying the remains of an ancient Maya settlement in Belize. This is an aerial photo of the archaeological site facing east. The white smudges are ancestral Maya mounds. (©2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH / University of Illinois )

Plowing Didn’t Destroy Much of the Maya Settlement

While the plowing has caused some diminishment of the upper level of the ruins, a surprisingly large treasure of artifacts and structural elements have been recovered during the ongoing excavations. Especially revealing have been the ceramic sherds that were recovered in abundance, which the archaeologists used to date the site to the Maya Classical Period. This era lasted from 250 to 900 AD and is recognized as the Golden Age of the prosperous and powerful Maya Empire, which at its peak spread far and wide across the lands of modern-day southern Mexico and northern Central America.The researchers were able to narrow down the time frame of this particular Maya settlement to the 250 to 600 AD time frame, which is considered the Early Classic Period. This is when the Maya launched many of their most ambitious monumental construction projects , and it is also the time when the greatest cities of the Maya Empire were constructed.

Petr

Administrator

Here are some more modern-looking Mennonites - I wonder if they are Trump supporters, with those red hats:

mexiconewsdaily.com

mexiconewsdaily.com

The young men with a butcher shop in Cuauhtémoc grilled meat over a pothole on the Manitoba Commercial Corridor highway and then offered commuters tacos. CARNES HILDEBRANDT/INSTAGRAM

In an attempt to shame local authorities about the state of the Manitoba Commercial Corridor in Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua, two butchers whose business sits along the stretch of road decided to host a barbecue.

Two young men with Carnes Hildebrand, part of the local Mennonite business community, filled one of the highway’s giant potholes with charcoal, placed a grill on top to cook meat and warm tortillas and proceeded to give away tacos to passersby.

After they uploaded a video of the stunt to their Instagram account, it went viral on the internet.

While not explicitly stated as such in the video’s description on Instagram, the video appears to have been a sarcastic attempt to get the attention of local authorities about the road’s condition. The local Mennonite community that makes up the majority of people in the area says the government has not done its part to maintain the corridor, which is the most visited place in Cuauhtémoc.

The pothole grill in Cuauhtémoc. FRANCES WIELER

The strip of highway is lined on either side with hundreds of warehouse-like stores selling farm equipment, industrial materials, clothing, even local Mennonite cheese, famous in this part of Mexico. There is also a Mennonite museum and several Mennonite suburbs and farms along the roadway.

Despite the road’s popularity, this particular stretch of paved highway is currently little more than a dirt road, as is apparent in the video, where one can see cars passing at highway speed near the young men as they prepare their barbecue.

In May, local officials announced a mobility plan with participation from Mennonite community leaders to rehabilitate and renovate the Manitoba Commercial Corridor after several fatal accidents took the lives of community members. That plan includes creating new crossings, more roundabouts and repaving various kilometers of the highway at a cost of almost 2 billion pesos (US $1.5 million).

A pothole in Chihuahua proves perfect for grilling some meat

Apparently meant to shame local officials into action, a pair of meat vendors offered up tacos cooked over one of a local road's many holes.

The young men with a butcher shop in Cuauhtémoc grilled meat over a pothole on the Manitoba Commercial Corridor highway and then offered commuters tacos. CARNES HILDEBRANDT/INSTAGRAM

A pothole in Chihuahua proves perfect for grilling some meat

The 'pothole barbecue' seems to have been intended to shame local officials about poor road conditions

Published on Wednesday, August 24, 2022In an attempt to shame local authorities about the state of the Manitoba Commercial Corridor in Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua, two butchers whose business sits along the stretch of road decided to host a barbecue.

Two young men with Carnes Hildebrand, part of the local Mennonite business community, filled one of the highway’s giant potholes with charcoal, placed a grill on top to cook meat and warm tortillas and proceeded to give away tacos to passersby.

After they uploaded a video of the stunt to their Instagram account, it went viral on the internet.

While not explicitly stated as such in the video’s description on Instagram, the video appears to have been a sarcastic attempt to get the attention of local authorities about the road’s condition. The local Mennonite community that makes up the majority of people in the area says the government has not done its part to maintain the corridor, which is the most visited place in Cuauhtémoc.

The pothole grill in Cuauhtémoc. FRANCES WIELER

The strip of highway is lined on either side with hundreds of warehouse-like stores selling farm equipment, industrial materials, clothing, even local Mennonite cheese, famous in this part of Mexico. There is also a Mennonite museum and several Mennonite suburbs and farms along the roadway.

Despite the road’s popularity, this particular stretch of paved highway is currently little more than a dirt road, as is apparent in the video, where one can see cars passing at highway speed near the young men as they prepare their barbecue.

In May, local officials announced a mobility plan with participation from Mennonite community leaders to rehabilitate and renovate the Manitoba Commercial Corridor after several fatal accidents took the lives of community members. That plan includes creating new crossings, more roundabouts and repaving various kilometers of the highway at a cost of almost 2 billion pesos (US $1.5 million).

Lord Osmund de Ixabert

I X A B E R T.com

The Doukhobors of Canada are in abundant proliferation in my vicinity. My interactions with their male constituents form a part of my daily existence. They are all, Intriguingly, conversant in Russian in this region, with a substantial number among them utilising English as well, howbeit marked by a noticeable Russian accent. It has been communicated to me that their variant of Russian retains a certain archaic quality, a linguistic facet that I aim to assimilate, intending to augment my Russian language proficiency through their tutelage, thus allowing me to mirror the vernacular of classical Russian literature.

The Doukhobors continue to adhere strictly to Christian shariah law, with their women donning hijabs & maintaining silence within the church premises. Not once have I observed any among them wearing protective masks during the entire course of the 'Covid19' charade. Their culture is undeniably steeped in Russian traditions & they bear their ethnic identity with pride. However, their detestation for Putin seems to match their aversion for the Czar & the Soviet Union, with political affiliations otherwise largely absent.

A striking attribute of the Doukhobors residing here is their non-compliance with tax regulations. They forego government-issued identification, driver's licenses, & social security numbers, thus liberating themselves from the confines of the system. Instead of purchasing land like the majority of the populace, they appropriate it, thus positioning themselves outside the societal norms to a degree that may see them endure beyond a system collapse.

Their resistance to assimilation is noteworthy, given their Aryan origins & resemblance, & their residence within a majority Aryan nation. Unlike the Jews, who possess the leverage of distinguishing themselves based on their religious beliefs, the Doukhobors, being Protestants residing within Christian communities & countries, could have easily assimilated into the mainstream. My personal observations, however, indicate their thriving existence, with their population appearing to surpass the official estimates, a fact tacitly acknowledged within the official Canadian statistical data.

A significant portion of the Doukhobors I encounter are of a younger demographic, tending to marry & procreate during their early years, mirroring the natural human tendency for women to bear children between the ages of 13 to 18. Observing them in larger congregations or in public marketplaces, one cannot help but notice the relatively high proportion of young women, invariably adorned in hijabs, who already have three or four offspring despite their young age, a stark contrast to mainstream society where women typically embark on motherhood at a later age.

From a demographic standpoint, & in the context of cultural preservation, it is decidedly worthwhile to study this people's ways & other similar communities, as well as Islamic societies & their laws & Koran. The mechanisms that promote the preservation, growth, & expansion of their communities are indeed worthy of replication by any community with similar aspirations for self-perpetuation, regardless of their religious orientation.

The Doukhobors continue to adhere strictly to Christian shariah law, with their women donning hijabs & maintaining silence within the church premises. Not once have I observed any among them wearing protective masks during the entire course of the 'Covid19' charade. Their culture is undeniably steeped in Russian traditions & they bear their ethnic identity with pride. However, their detestation for Putin seems to match their aversion for the Czar & the Soviet Union, with political affiliations otherwise largely absent.

A striking attribute of the Doukhobors residing here is their non-compliance with tax regulations. They forego government-issued identification, driver's licenses, & social security numbers, thus liberating themselves from the confines of the system. Instead of purchasing land like the majority of the populace, they appropriate it, thus positioning themselves outside the societal norms to a degree that may see them endure beyond a system collapse.

Their resistance to assimilation is noteworthy, given their Aryan origins & resemblance, & their residence within a majority Aryan nation. Unlike the Jews, who possess the leverage of distinguishing themselves based on their religious beliefs, the Doukhobors, being Protestants residing within Christian communities & countries, could have easily assimilated into the mainstream. My personal observations, however, indicate their thriving existence, with their population appearing to surpass the official estimates, a fact tacitly acknowledged within the official Canadian statistical data.

A significant portion of the Doukhobors I encounter are of a younger demographic, tending to marry & procreate during their early years, mirroring the natural human tendency for women to bear children between the ages of 13 to 18. Observing them in larger congregations or in public marketplaces, one cannot help but notice the relatively high proportion of young women, invariably adorned in hijabs, who already have three or four offspring despite their young age, a stark contrast to mainstream society where women typically embark on motherhood at a later age.

From a demographic standpoint, & in the context of cultural preservation, it is decidedly worthwhile to study this people's ways & other similar communities, as well as Islamic societies & their laws & Koran. The mechanisms that promote the preservation, growth, & expansion of their communities are indeed worthy of replication by any community with similar aspirations for self-perpetuation, regardless of their religious orientation.

All factors particular to their society that contribute to their thriving fertility rates & the perpetuation of their culture throughout the ages must be diligently studied, with the goal of implementing these factors systematically within our own emerging communities.

Some of the factors which aid the Doukhabours, Amish, Mennonites, Mormons, & a smattering of other minority Christian communities around the world, include the following:

- The adherence of women to Christian Sharia law: their customary donning of the hijab, their reticence within the church, & the absence of female leaders.

- The clear distinction in labour division among the sexes.

- A preference for rural settings over urban locales.

- A tendency towards early marriage & associated heightened fertility rates, with ages between 12 & 16 seeming to be the demographic sweet spot.

- A general disdain towards contraception, abortion, masturbation, & sexual promiscuity.

- A proclivity towards undersexualisation as opposed to hypersexualisation.

- The avoidance of vaccinations seems to be linked with higher fertility rates.

- Any linguistic or dialectic barriers that differentiate them from the general population essentially serve as a buffer against external propaganda & immorality.

- Insulation from the outside world, both geographically & in terms of lifestyle choices.

- Pacifism: Despite my personal nonpacifist stance, most of the successful communities have adopted pacifist tendencies. This often manifests as a façade of pacifism, which effectively keeps government interference at bay—a pressing concern considering their noncompliance with taxes & govt. identificaiton, & their intent to create a parallel society & economy to outlive the prevailing régime.

- Whether polygamy or monogamy results in a higher fertility rate & which of the two has a more eugenic effect should be studie

I maintain an interest in any additional factors that may provide these communities with a demographic advantage. These factors could include specific religious beliefs conducive to demographic growth, the unique manner of women & children's education, exposure to pollutants affecting fertility, inter alia. Surely a plethora of factors warrant our attention.