Petr

Administrator

Why Serbia’s President Is a Threat to Europe

Aleksandar Vucic’s authoritarian government is aiding Russian and Chinese propaganda and allowing genocide denialists to celebrate war criminals.

Why Serbia’s President Is a Threat to Europe

Aleksandar Vucic’s authoritarian government is aiding Russian and Chinese propaganda and allowing genocide denialists to celebrate war criminals.

By Florian Bieber, the coordinator of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group and holds the Jean Monnet chair in the Europeanization of Southeastern Europe at the University of Graz, Austria.

Police officers walk past a mural depicting former Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic in Belgrade on Nov. 9, 2021. OLIVER BUNIC/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

JANUARY 5, 2022, 11:41 AM

In November and December 2021, thousands of Serbian citizens took to the streets, blocking key roads for three weekends to protest a proposed law facilitating expropriation seen as favoring a large-scale lithium mine planned in Western Serbia by the multinational company Rio Tinto.

The protesters are primarily concerned about the lack of transparency around the mine project; they also fear serious environmental damage and large-scale corruption. During the first protests, thugs with sticks beat protesters and tried to drive through the protests in a bulldozer in Sabac, the closest city to the planned mine. They were driven to the location in government cars, and there was little doubt that they were threatening demonstrators on behalf of the regime.

Today, no decision can be taken without Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, who features on talk shows for hours on a weekly basis on all main TV channels. He heralded the deal as a major investment and offered it direct political support. Nevertheless, the demonstrations highlight that while Vucic might have absolute command of the country—188 of the 250 members of parliament were elected on his party list and his party controls nearly every municipality in the country—his rule is not uncontested.

After the protests gained momentum, Vucic at first appeared to concede and withdraw support for the project, but soon afterward, on Dec. 27, 2021, he reiterated his support and insisted it would go ahead after all.

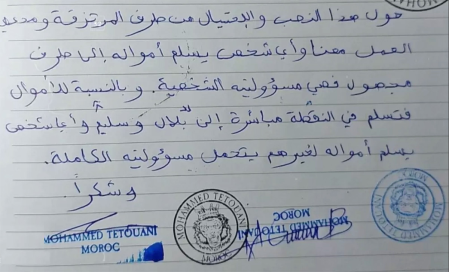

Another spectacle in recent weeks underlined the menacing side of Vucic’s regime. In downtown Belgrade, there is a stain on a wall that does not seem to come off. It is a mural of Ratko Mladic, the war criminal responsible for genocide in the eastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica in 1995.

In July, the portrait of Mladic—who is serving his life sentence after being sentenced by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia—appeared in Belgrade, as such portraits did in many other towns in Serbia and the Republika Srpska, the entity of Bosnia he helped to create through war crimes. These were not the first portraits of Mladic to pop up, but they are appearing with increasing frequency, and earlier cases enjoyed less official protection.

Citizens keep trying to paint over the portraits, but diligent thugs keep restoring the most prominent portrait in a central Belgrade neighborhood. When two activists threw eggs at the portrait, they were arrested by plainclothes police. While nationalist tabloids close to the regime openly claim Mladic was a hero, the Serbian government has been protecting the mural without openly endorsing its motive.

By allowing the murals to be protected by unidentified thugs, the government is pandering to the nationalist electorate, while denying any responsibility for them and thus protecting its pro-European credentials. The closest it came to publicly supporting Mladic was when Minister of the Interior Aleksandar Vulin paid a visit to the mural after the arrests on Nov. 9, 2021.

The nationalist and authoritarian character of the Serbian government poses a threat for Serbia and the region. Vucic’s claim to be a pragmatic, mainstream European conservative might have seemed convincing in his first years in power, but it increasingly sounds hollow.

Vucic’s authoritarian course has increasingly distanced Serbia from the West and the European Union. While his party was supported by Western embassies in its first years, in hopes of promoting a pragmatic politician with whom one can do business, Vucic and the media his government controls have been promoting an anti-Western line.

By now, Serbia is an outlier in the Western Balkans. A regional poll commissioned by the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group shows that 80.4 percent of the region’s citizens want their country to join the EU; in Serbia, that number is just 53.2 percent.

China and Russia are viewed as bigger supporters and more widely trusted, whether it’s due to the COVID-19 vaccines they donated or their leaders. This view has been compounded with the pandemic, with China being seen as the main provider of assistance—even though Belgrade bought the vaccines from Beijing, and there is no public information on the price paid—and the United States and the EU viewed as spreaders of fake news.

This is a result of an intense anti-Western campaign from pro-government media, which continuously accuse Western governments, as well as independent media, including the CNN affiliate N1, of being anti-Serbian propaganda outlets.

Even when it comes to Serbs’ support for the EU, there is a clear authoritarian slant. Surveys show the most popular world leader, after Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, is Hungary’s autocratic Prime Minister Viktor Orban; in other words, when Serbs look to Europe they look to Budapest, not Berlin.

While in 2015 Vucic dismissed Orban for his hostility to migration and described Serbia a more European country than some EU members—a clear dig at Hungary—he has since replaced his cozy relationship with then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel with a friendship with Orban.

While Germany remains an important ally in terms of economic investments and due to its weight in the EU, Vucic gets along better with a fellow autocrat. Orban promises a closer relationship with the EU for what Serbia under Vucic is—a nationalist and authoritarian regime—while Germany only offers this for what Serbia under Vucic pretends to be: a pro-European factor of stability. The new German government, with Annalena Baerbock as a Green foreign minister, is likely to push harder on issues of rule of law and democracy in Serbia.

The turn against the West, combined with Vucic’s authoritarian control, matters beyond Serbia. While attitudes elsewhere in the region are still very different, there is a real threat of contagion. Besides being at least twice as large as any other country in the Western Balkans, Serbia borders all others (except Albania) and seeks to shape the region in two ways.

First, it presents itself as a regional leader through the “Open Balkan” initiative of regional integration, the idea of an integrated region based on open borders known also as “Mini-Schengen” that would give Serbia the largest economic benefits and also tie the rest of the region more closely to it. Vucic’s international and regional policy is still based on the faint echo of socialist Yugoslavia, which as a country did manage to punch above its weight.

The other and somewhat conflicting approach is the so-called Serbian world—a term borrowed from Russia and basically describing a Serbian sphere of influence based on ethnicity. Serbia is influential through Serb parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Kosovo. Even if it does not control all of them completely, this allows Serbia to shape the domestic politics of its neighbors and block key decisions.

By building a sphere of influence, Serbia can spread its authoritarian anti-Western policies throughout the region. In Kosovo’s recent regional elections, the outcome was far from clear in majority-Albanian municipalities, with the ruling Vetevendosje party of Prime Minister Albin Kurti taking a beating. This showed vibrant political contestation in the Albanian-majority regions of Kosovo, unlike in the Serb-majority areas. In the 10 majority-Serb municipalities, the Serb List, controlled by Belgrade, won across the board through a combination of intimidation and corruption. In many places the party was not challenged and won up to 100 percent of the vote.

Serbia also gained influence across the region in 2021 by providing vaccines and allowing citizens of other countries to get vaccinated in Serbia. This was especially important for citizens from neighboring Bosnia, North Macedonia, and Montenegro, who lacked initial access to vaccines due to the slow rollout of COVAX, the EU-supported global vaccination program. This was a pragmatic decision—Serbia secured vaccines from China, Russia, and the West, but many citizens refused to get vaccinated due to strong anti-vaccine sentiment and low trust in the government. Making vaccinations available across the region gained it considerable sympathies in neighboring countries.

While the EU helped to secure the bulk of vaccines in the region, it was late and failed to highlight and communicate its assistance when it arrived. As a result, Serbia played the regional role in vaccine diplomacy that Russia and China did elsewhere, with a similar impact.

According to soon-to-be-published survey results from the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, Serbia is rated as the greatest help during the pandemic by citizens in Bosnia, mostly in the Republika Srpska, but also in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where relatively few Serbs live, Serbia is second only to the EU, Montenegro, and North Macedonia. In North Macedonia, where ethnic ties do not matter, more citizens expect help in the battle against COVID-19 to come from Serbia than the EU.

While there is nothing wrong with regional solidarity, when it is promoted by an autocrat who has been working closely both with external actors to maximize his support and with authoritarian leaders in the EU, this increased influence does not bode well. Just as Orban has been helping to promote like-minded leaders in the EU through financial assistance, diplomatic backing, and supporting friendly media, Vucic is seeking to extend his influence across the Western Balkans in similar ways.

This move makes him indispensable for Western interlocutors and helps him stay in power. In the process, it normalizes the authoritarian, anti-Western, and nationalist worldview that permeates the party and media he controls. This risks undermining democratic and liberal governments across the region and weakening the influence of the EU there, while encouraging a government that has been stoking nationalist tensions.